Ajai Sreevatsan and Deepa H Ramakrishnan. October 03, 2011.

Environmental consequences of green cover loss are wide ranging.

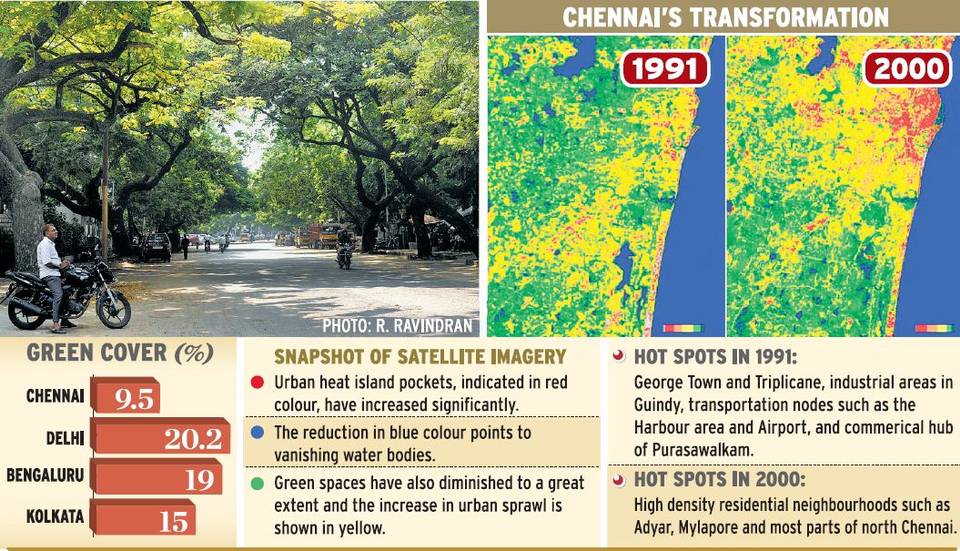

The city holds the dubious distinction of being one of the least green metros in the country. With a green cover spread over just 9.5 per cent of its geographic area, Chennai’s dream of achieving the goal of 33 per cent urban forest cover by 2012, as envisaged in the National Forest Policy (1988), might remain simply a pipe dream.

The city’s fall from grace has been dramatic. Experts point to the decade immediately after the economic liberalisation, especially between 1997 and 2001, when the city lost up to 99 per cent of its green cover in some parts. The built-up area in the city nearly doubled in that short period, show remote sensing satellite images.

Koothapiran, known as ‘Vanoli Anna’ on All India Radio, recalls how he used to walk from Adyar to the Mylapore Kapaleeswarar temple to listen to Navaratri concerts. “The entire stretch used to be lined with trees and there used to be nearly 400 coconut palms around the temple tank. But over the years we have lost many trees to development.”

The environmental consequences of the reduction in green cover has been wide ranging – increase in air pollution, ground water depletion, frequent flooding during the monsoon and an overall rise in temperature in the city as a result of concretisation.

“Air quality in the city has markedly deteriorated in the past decade,” says R. Sridharan of the Asthma Allergy Resource Centre. “More young children are showing asthmatic symptoms than ever before,” he adds. Studies show that residents of the Chennai Metropolitan Area (CMA) would collectively breathe in over 4,000 lakh kg of vehicular emission annually if drastic improvements are not made. Monsingh Devadas, Dean, School of Planning and Architecture, Anna University, says that the green cover dwindled in the city due to rapid and unplanned urbanisation. “Open spaces came down as the built-up area increased.”

‘Urban heat island’

He says that the combination of dense built-up areas and reduced vegetation has resulted in an increase in urban temperature, a phenomenon known as the ‘urban heat island’ effect. “Since concrete and asphalt absorb the heat, unlike trees which re-radiate it back into the atmosphere, the number and intensity of hot spots in the city is increasing. People are being forced to spend more on electricity costs, especially to run air-conditioners at night,” he adds.

On the other hand, Delhi’s turn-around offers a picture in contrast. Over the past 10 years, the national capital’s green cover expanded by nearly 10 times. Govind Singh of Delhi Greens, an NGO, says that the city has realised that tree plantation drives would be successful only if the local population is involved. “The events are widely publicised and celebrated like a festival. The 2,800 eco-clubs that function in schools and colleges have also played a big role.”

After steadily declining for three decades, ground water levels in Delhi have stabilised, air quality has improved and noise levels have reduced. Developing a green belt around each residential locality that can act as a noise barrier is now official policy, Mr.Singh says. “If we want to live in sustainable cities, we must understand that trees are an integral part of the landscape, not an obstruction.”

Plantation without vision

Questioning Chennai’s own afforestation efforts, Mr.Devadas, says the current urban tree cover improvement efforts are often not carried out strategically. Hence, trees are standing as a green element rather than contributing to environmental benefits. Trees can improve the urban environment only when it is spatially integrated within the city planning, he says.

This year, the Forest Department plans to plant six lakh saplings in Chennai region, including 25,000 inside the Vandalur zoo. Environmentalists emphasise that the saplings would have to be planted keeping in mind the 23 guidelines issued by the Urban Development Ministry for afforestation in urban areas. The guidelines specified in 2000 clearly state that an area of 6×6 inches is to be left un-cemented around trees to let them grow. They also specify that digging near trees is to be avoided.

R.Madhavan of the Environmental Society of Mandaveli says that maintenance and pruning is another major problem and the Chennai Corporation does not take adequate care. “Every tree that is taller than 25 feet requires attention ahead of the monsoon. Urban environments restrict their roots between the compound wall and the road. Trees can easily topple.” However, the civic body maintains that pruning is carried out on a regular basis across localities based on a time-table.

Having personally planted over 3,000 avenue trees, he also says that instead of making a big fuss about cutting trees, people must make a fuss about planting trees. The Chennai Metro Rail project alone is estimated to result in the loss of 17,000 trees. Over 35,000 trees were axed for the Delhi Metro, but the overall green cover still increased substantially. “The concept of a tree’s permanency does not exist. They also die, but ought to be replaced,” says Mr.Madhavan.

Click here to read this article on The Hindu website.